Previously we found that HMRC is hardly using powers to investigate, penalise and publicise tax advisers who enable tax abuse. Here we look at why these powers aren’t being used: a barrage of legal roadblocks; and holding back on naming and shaming.

***

When tax adviser Mr. B met with HMRC officers enquiring into one of his client’s tax returns, he had something surprising to say.1

According to court records, Mr. B explained to the officers that he had tried to help his client reduce his VAT bill by creating false purchase invoices for expenditure that his client’s business hadn’t actually incurred. As detailed in HMRC’s notes of the meeting, which the court accepted as accurate, Mr. B admitted that for years he had created invented invoices using real bills from two flooring companies, from which he had kept the letterheads, blocked out the details of the invoices, and photocopied new details into dummy documents. Deducting these fake costs against income tax and reclaiming the VAT had saved Mr. B’s client over £20,000 in taxes, HMRC told the court.

When the HMRC officer enquired about other invoices she’d noted, Mr. B told her that “they were all made up” too. He had decided to come clean, he said, because he expected that HMRC would find the fake invoices. (He also admitted in a later meeting, according to HMRC’s notes, that it had been his idea — insisting that his client did “not have sufficient knowledge to do this” himself).

This was no elaborate and contestable tax avoidance scheme. No offshore trusts or complex financial instruments. Just a small-scale, straightforward alleged deception: invoices for non-existent purchases, mocked up on the tax adviser’s own computer.

Arguably HMRC might have considered launching an investigation for possible fraud. Instead, they used a civil penalty procedure in place since 2012 to penalise tax agents responsible for “dishonest conduct”. On the face of it, a fairly straightforward case.

Nearly four years after his admission, however, Mr. B was still contesting that he’d done anything dishonest (“he did not commit a dishonest act”, he said in one of his appeals, “but merely tried to help [his client] which with hindsight was the wrong way to do it”). And HMRC still hadn’t been able to access the documentation from him needed for proof and a penalty – despite the adviser accepting that he had created false invoices worth tens of thousands of pounds.

A long and winding road

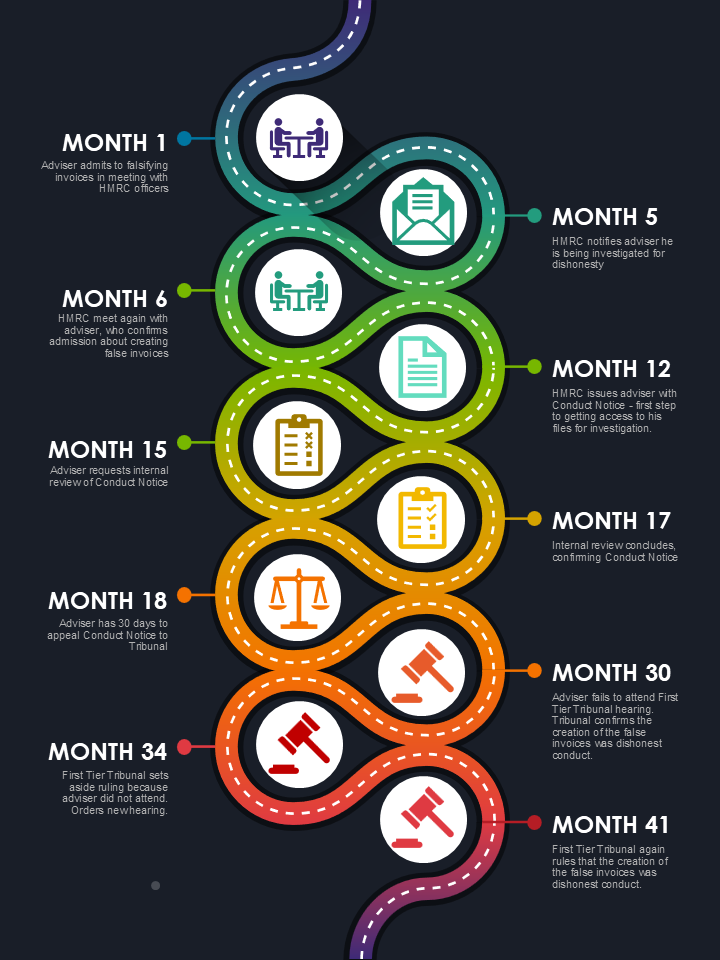

Though the details are lengthy, it’s worth looking at how this process went, because it’s a rare public window into one reason why HMRC’s armoury of powers against enablers of tax abuse have barely been used:

After all this, the process had only completed its first stage: enabling HMRC to issue a ‘File Access Notice’ to obtain the tax adviser’s documents for its investigation.

We don’t know exactly how the case went after this point. But the law will have required it to follow a process like this:

- The First Tier Tribunal ruling will have allowed HMRC to issue a ‘File Access Notice’

- Issuing this second notice must also be approved in advance by the Tribunal. Assuming that it approves, HMRC can then – finally – demand the documentation its investigation needs. (The tax adviser themselves can’t appeal the File Access Notice, though third parties like their clients can, adding another appeal stage to the process). Given the time that has likely now elapsed, and the adviser’s extensive pre-notification, some of this documentation may be gone by this stage

- At the end of its investigation, HMRC can fine a dishonest tax adviser between £5,000 and £50,000: a fixed penalty scale unrelated to the tax foregone, or the fees received by the adviser; hardly dissuasive in many cases

- Of course, this penalty can also be appealed, as with most civil penalties.

Safeguards or roadblocks?

The tale of an ostensibly straightforward case like Mr. B illustrates one reason why, according to HMRC, it can’t effectively use its powers against tax advisers who enable their clients to avoid and evade tax: a barrage of legal and procedural obstacles baked into the legislation.

Ordinary taxpayers who find themselves under HMRC scrutiny may also be surprised by the procedural magnanimity that the law accords to tax advisers suspected of dishonesty. HMRC can in most cases require taxpayers to provide any information or document “reasonably required by the [HMRC] officer for the purpose of checking the taxpayer’s tax position”, without prior notice and without tribunal pre-approval (though the taxpayer can still appeal it). Under the dishonest advisers regime, by contrast, tax advisers can’t even be compelled to provide documents without HMRC having first “determined” their dishonesty (often hard to do without access to documents), and there can then be two or even three appeals before HMRC can access that documentation – access which must itself be approved by a court.

HMRC has pointed to similar procedural obstacles in tackling tax advisers who operate abusive tax schemes. Before it can compel information from such ‘enablers’, HMRC has historically had to defeat the scheme, and settle all the tax bills of the scheme’s users. Legal changes in 2021 to unblock this problem don’t appear to have helped: as we discussed in a previous post, HMRC imposed fewer than five penalties on enablers of abusive tax schemes in each financial year from 2020 to 2024, and possibly none at all in some years.

Powers to name and shame enablers of defeated schemes – and to protect future unsuspecting scheme users – are similarly hedged with limitations. HMRC can only publish their details if the enabler has received 50 or more penalties for the defeated scheme, or penalties over £25,000. HMRC’s current name/shame list contains no names of such enablers at all.

‘Tourists photographing Westminster Abbey’

These obstacles aren’t accidental. They’re the result of negotiation and lobbying. That’s normal: stakeholders should be consulted as laws are created. Nonetheless, in the case of the dishonest tax advisers legislation used against Mr. B, powers originally proposed by HMRC were transformed over the course of three years of consultation.

The original 2009 proposals2 were modelled on HMRC’s standard powers to obtain information and documents about ordinary taxpayers’ tax affairs from third parties. These ‘Schedule 36’ powers already require Tribunal approval, though not necessarily notifying the taxpayer in advance. Nonetheless some parts of the tax industry compared the proposals to use them against dishonest tax advisers with overweening powers in the War on Terror: “The parallel with “anti-terror” legislation which enables over-zealous constables to arrest tourists photographing Westminster Abbey is too striking to ignore”, said the Association of Taxation Technicians.

In response to such criticism, over the next two years the offence itself was tightened, from ‘deliberate wrongdoing’ to ‘dishonest conduct’. The process of HMRC getting access to tax advisers’ papers was split into two parts (‘Conduct Notice’ followed by ‘Access Notice’), with two extra points for tax advisers to appeal HMRC’s actions to Tribunal. Penalties geared to the tax lost were replaced by a simple £50,000 maximum. The possibility of fining advisers’ firms was removed.

After all this, what arrived in Parliament was draft legislation explicitly encoding the lengthy and sometimes unworkable road described above. Similar stories can be told about the other measures against tax abuse enablers that sit largely or wholly unused on the statute book.

Meanwhile criminal prosecutions of tax evasion enablers and their firms are rare and falling. Fewer than five were prosecuted in 2023/24, down from 16 in 2018/19.

Time for a re-think

This year, with public finances under pressure and new commitments to tackle tax abuse, HMRC is proposing to return its powers against dishonest tax advisers and tax avoidance promoters to something more like its original proposals: shortening timelines, reducing appeal points, and increasing penalties.

TaxWatch, broadly, agrees. (The tax profession’s membership bodies, except on penalties, do not).3 Tilting the balance of power between investigator and investigated always requires careful thought, as tragedies like the Post Office scandal have taught us. In this case, however, there are still appeal safeguards, as well as counterbalancing public interests: not just the tax revenues that might be recovered, but also the fact that penalties and publicity protect prospective clients from delinquent tax advisers. And the powers that HMRC are looking to streamline are already more lenient alternatives to criminal prosecution in situations of serious misconduct, and in some cases demonstrable dishonesty.

Hands tied, or holding back?

The long and winding road isn’t the only story.

Sometimes tax abuse enablers are successfully penalised. But even then, HMRC generally holds back from publicising or naming them, even when it has legal powers to do so.

For instance, since 2013 HMRC has been able to publish the names of all tax agents penalised more than £5000 for dishonest conduct – essentially those who didn’t self-disclose. We know that there have been at least a few penalties of this kind and size, but it appears that HMRC has never published their names.

Though this may be as much about coordination as reticence, it leaves a significant gap. As TaxWatch’s own professional standards complaints have demonstrated, the tax profession’s membership bodies sometimes don’t sanction or expel members even when they have been penalised for serious misconduct. In any case, a third of the UK’s 85,000 tax advisers don’t belong to any professional body at all. So if HMRC doesn’t use its own disclosure powers, tax advisers that have acted dishonestly or enabled tax evasion can keep it secret from current and prospective clients, and continue to practice.

Making it work?

What would effective measures look like to tackle tax advisers who enable tax evasion and avoidance?

TaxWatch’s recent submission to HMRC sets out some practical ideas. Broadly, we need:

- deterrence: meaningful and workable penalties, backed up by the realistic threat of criminal prosecution, for those who enable tax abuse and too often walk away when their clients get caught.

- transparency: a centralised register that the public can search – as they can with other professions – to see whether a tax adviser has been penalized, prosecuted, or flagged as a tax avoidance promoter. Except in exceptional cases, publishing this information should be mandatory, and pulled together from across the current collage of at least eight distinct tax law regimes against delinquent tax advisors. (TaxWatch will be exploring in the near future how this information can be combined with open data to shine a light on the networks of tax advisers who promote tax avoidance and evasion).

- sanctions that stick: To stop delinquent tax advisers from walking away from penalties, firms and their directors should be liable for penalties incurred by their employees. Penalties should be geared to firms’ revenues. And data analytics should flag when sanctioned tax advisers jump ship to a new or different firm.

But we also need institutional commitment to penalize and prosecute enablers of tax abuse. Investigators in every major tax evasion case should have internal incentives or requirements to investigate the potential liability of the advisers and facilitators, alongside the taxpayers themselves. Otherwise only the simplest, small-scale facilitation of tax evasion will be penalized. The architects of schemes and frauds with huge impacts on the public purse, meanwhile, will still have little to fear.

TaxWatch’s submission to HMRC’s recent consultation on powers and penalties against tax advisers who facilitate non-compliance is here.

***

1 TaxWatch tried to contact Mr. B and his client for comment on this piece, but was unable to do so. The details above are taken from published judgements of the First-Tier Tribunal, though since we were unable to get a response from Mr. B we have anonymised the details here.

2 Initial proposals in 2009 aimed to replace simpler (though similarly circular) measures on the statute book since the late 1980s that provided for penalties on those who knowingly assisted the preparation of an incorrect tax return, and for obtaining papers of tax accountants thus penalised.

3 The Institute for Chartered Accountants of England and Wales, the largest membership body, actually wants tax advisers who adhere to their own Code of Conduct to be exempt from HMRC’s new powers against dishonest conduct.

Main image: Theo Paul / Flickr CC BY 2.0