On Saturday the Sunday Times published its annual ‘Tax List’ – the celebratory counterpart to its better known ‘Rich List’, claiming to list the people that are the country’s top individual taxpayers.

As in previous years, the list has fueled claims that millionaires and billionaires are paying an outsized proportion of the UK tax take. And before the doom and gloom – there is much to celebrate here. Some high-income or high-wealth people on the list do clearly pay their fair share: avoiding games with residence or domicile; not constructing elaborate offshore structures through trusts and other vehicles; treating income as income, like the rest of us.

To take a straightforward example: Denise Coates CBE of gambling giant Bet365 (number five on the list) may have been paid nearly £300 million last year, and we can argue about whether that’s a good or a bad thing. Coates is nonetheless still resident in the UK, and the fact of having taken a whopping £104 million of that income through the payroll means the public purse gets more money as income tax and NICs than from more dividend-heavy remuneration.[1]

But some of the Tax List laureates being lauded this weekend will have the opportunity to reduce their personal taxes in ways not available to most of us. There are individuals getting paid via service companies in zero-tax jurisdictions, instead of taking salary locally. One in nine of the Tax List ‘Top 100’ appear to live abroad: in some of those places they’ll pay tax locally, but in others, like the UAE and Monaco, they presumably enjoy those jurisdictions’ zero percent income and capital gains taxes.

Audio: TaxWatch’s Mike Lewis myth-busts the Sunday Times Tax List with LBC’s Nick Abbot

Credit where credit’s due

There’s no suggestion that such steps are unlawful. (Though the Sunday Times even included former F1 boss Bernie Ecclestone in its 2024 ranking of heroic taxpayers, reflecting Ecclestone’s £652 million tax bill in 2023…thanks to his record-breaking conviction for tax fraud which required him to pay back taxes and penalties on £400 million of income concealed offshore for nearly twenty years).

But the availability of a myriad ways for wealthy individuals to reduce their personal tax bill, whether aggressive or pedestrian, does mean that it is impossible for us – or the Sunday Times – to know how much tax most of the people on this list have actually paid on their income and gains. Unlike in Norway, where individual (and corporate) tax returns are published every year for anyone to look at, in the UK and most other countries individuals’ tax affairs are vigorously protected by our tax authority. Which is not the impression given by the Sunday Times’ unqualified ranking of these individuals and their purported tax bills.

Does the Sunday Times try to take these uncertainties into account? On the contrary, included in the tax contribution of each individual on its list are millions of pounds of taxes that are visible (through published company accounts) but are not paid by the individuals themselves.

Since individuals’ tax bills are secret, the Tax List simply adds up all the corporation tax, dividend tax, capital gains tax, employers’ national insurance tax and other taxes (such as gambling and alcohol duties) paid by the companies these individuals own. It attributes these company-paid taxes in their entirety to the individuals that own the companies, in proportion to their shareholding.

In other words, most of these taxes aren’t paid by the individuals themselves, and aren’t taxes on their individual incomes or gains. To attribute those taxes economically to the individual owners is to argue that corporate taxes fall entirely on company shareholders – contrary to almost every mainstream economist who considers that corporate taxes fall ultimately on a mix of shareholders, workers and customers (with low-tax advocates usually claiming that workers, not shareholders, bear the largest share). And to attribute them morally to the individual owners is to argue that the income, profits and growing value of a company should be attributed entirely to the work and genius of its largest shareholders. While not wanting to denigrate entrepreneurs, that’s a bit of a slap in the face for everyone else who works for those companies or buys their goods.

Till the pips squeak?

But even if the Sunday Times’ figures were 100% accurate reflections of these individuals’ personal tax bills, there’s a bigger question about what lesson we should take away from the List. The Sunday Times uses the immense sums attributed to each of the 100 individuals on the List to argue that wealthy individuals pay a huge, even disproportionate, share of the UK tax take. Though most of their own figures don’t reflect personal tax at all, they nonetheless cite figures from HMRC that the UK’s top 1 percent by income paid over a quarter of all income tax in 2024-25. But that just tells us that taxable income and gains are skewed in the UK towards a very small number of very rich people. The meaningful question – which the Tax List can’t answer – is whether the super-rich pay a higher percentage of their income and gains in taxes than those lower down the wealth scale.

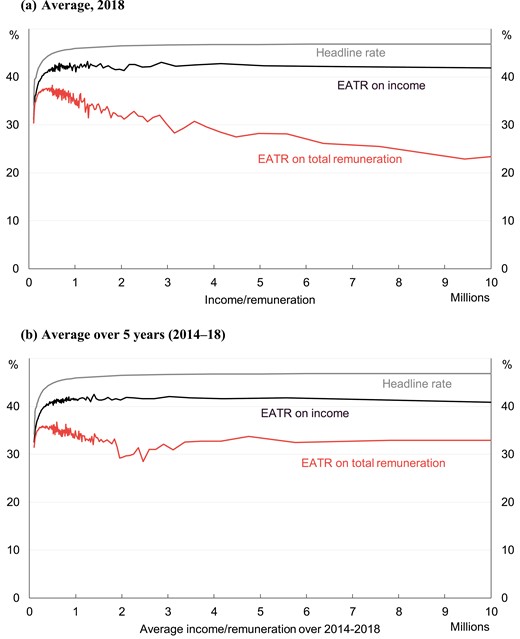

That’s not a mystery, thanks to detailed work by the Centre for the Analysis of Taxation (CenTax) affiliated to the University of Warwick and the London School of Economics. Looking at anonymised tax returns from 2014 to 2018, CenTax has shown that on average, those with income and gains over £500,000 tend to pay less tax than lower down the income scale:

Taking into account taxable gains as well as income, EATRs [Effective Average Tax Rates] peak at 38 per cent at remuneration of £500,000. At this level, effective rates are already almost 7pp below the average rate on earnings of the same amount. The personal tax system is regressive above £500,000: above this point, effective average rates on total remuneration start declining, even as the headline rate continues to rise.

In some years, such as 2018, average effective tax rates fell significantly as incomes increased from around £200,000 to £10 million. Even including the corporate taxes underling individuals’ dividends doesn’t significantly affect the shape of the curve.

This is not the message that the Sunday Times’ Tax List conveys – but it is one grounded in data from thousands of people’s actual tax returns, which the Tax List is not.

TaxWatch takes no position on tax rates, or on how different forms of income and gains should be taxed. But what CenTax’s research shows is that there are many ways – entirely legally – for the very wealthy to reduce their own tax rates below that of significantly less wealthy people: whether through their own tax-structuring efforts, or the simple effect of the tax system on different forms of income.

There are plenty of tax heroes on the Sunday Times’ list: entrepreneurs and growth creators who, like the members of ‘Patriotic Millionaires’, are “proud to pay and here to stay”. The idea of celebrating them is a good one. But thanks to the way the List works, their contribution doesn’t get any more recognition than those who are actively shrinking their UK tax bills.

Meanwhile HMRC estimates that the ‘wealthy tax gap’ – the tax that goes unpaid by the 850,000 people with incomes over £200,000 or assets of over £2 million in any of the last three years – is rising, and is now roughly the same as the tax gap for all other individual taxpayers combined (around 35.4 million people).

The war on tax avoidance and evasion is far from over, and it’s a little premature to be handing out medals.

Source: HMRC, Measuring Tax Gaps

[1] Though, obviously, the tax advantage of being paid in dividends has also shrunk in recent years with changes in corporation tax and dividend tax rates and thresholds. TaxWatch asked Bet365 for comment on the figures given here, but has not received a response.