For a PDF version of this briefing, click here

Executive summary

- Large online businesses – search engines, online retail platforms, social media – can generate revenues from users and customers while having limited or no taxable presence where those users and customers are located. This makes it possible to reduce their tax liabilities in ways that ‘bricks and mortar’ businesses cannot.

- To compensate, the UK and around 30 other countries have introduced Digital Services Taxes (DSTs) over the last decade. The UK’s Digital Services Tax (DST) is a 2% levy on the largest online tech companies’ revenues attributable to UK users, wherever those revenues are ultimately booked.

- DSTs were only intended as a temporary ‘fix’ but have remained due to deadlock in the international tax agreement intended to replace them. The US government announced in early 2025 that it would drop out of this international agreement, while also renewing threats of additional tariffs, technology embargoes and punitive ‘revenge tax’ escalators against countries, and their citizens and companies, which refuse to abolish DSTs.

- The US tech industry has strongly supported these retaliatory measures, against opposition from other US and international business sectors. Tech industry representatives have specifically singled out the UK DST in their lobbying.

- UK law obliges the UK government to conduct a review of the DST and lay it before Parliament by the end of 2025. The UK has already discussed changes or abolition of the UK DST with the US, and the Prime Minister has refused publicly to rule out changes. With pressure from the US government and the US tech industry, it is possible that the 2025 review may be an occasion to reduce or abolish the DST.

- New revenue estimates produced for this briefing using online advertising and retail statistics suggest that – if retained – the UK DST could generate revenues of between £4.4bn and £5.2bn over the course of this parliament: a modest amount compared to overall business taxes and the revenues of large online tech companies, but equivalent (for example) to the cost of training between 108,000 and 128,000 new nurses (25-29 percent of the current NHS nurse workforce).

Key claims about the UK DST made by the US Government and the US tech industry are incorrect:

- The US government report whose findings prompted the threat of tariffs against the UK in 2021 claims that the UK DST was deliberately designed to apply to US companies while exempting UK businesses. It bases these claims on statements by MPs, including Jeremy Corbyn and Margaret Hodge, who were in opposition when the tax was developed and introduced, and could not possibly have been involved in its design. We have identified at least one large UK online retail platform which also pays the UK DST.

- The US President has claimed that DSTs exempt Chinese tech companies. However, DSTs are based on sales revenues, and corporate reporting suggests that in Q2 2025 the Chinese social media company Bytedance outranked US companies as the world’s number 1 social media company by sales for the first time. Since major online marketplaces and content providers used by UK consumers now include those headquartered in China, Singapore or related financial centres, from Shein and Temu to TikTok, it is very likely that abolishing the UK DST would in part benefit Chinese and other non-US internet giants that are amongst the sector’s fastest-growing members.

- The leading US tech industry group, whose members include all major US tech companies, published statistics in July 2025 claiming that all UK DST revenue (and that of the French, Italian and Spanish DSTs) is paid by US-headed firms. In fact, the first ever statistics about the nationality of the companies within scope of the UK DST, obtained by TaxWatch through Freedom of Information laws, show that 37 percent of the companies or corporate groups assessed to be liable for the UK’s DST are not headquartered in the US, 34 percent of those which submitted a DST return in 2023/4 (the latest year available) are not US-headquartered, and 28 percent of those which paid a DST liability in 2023/4 are not US-headquartered.

- US-headed groups may still provide a greater proportion of UK DST revenues by value than their numerical proportion, in accordance with their larger revenues in markets with DSTs. However, to argue that the DST discriminates against US companies in this way is to argue that a flat-rate tax discriminates against taxpayers simply because they make more taxable profits or revenues.

Please note: nothing in this briefing should be taken to imply any unlawful activity or other wrongdoing on the part of any legal or natural person mentioned.

Introduction: what are digital services taxes?

Large, global online service providers – social media, search engines, e-commerce, cloud providers – pose a challenge to corporate taxation.

Corporate tax is organized according to businesses’ presence within national borders: international tax rules envisage, broadly, that businesses should be taxed in the jurisdictions where their assets and profit-generating activities are located. Unlike many other business sectors, however, large global tech businesses – social media companies, online retail platforms and search providers – can generate income from users and customers in a country without having a significant taxable presence there at all. Meanwhile their subsidiaries in much lower-tax jurisdictions can book sales, own assets – especially intangible assets like software, trademarks, customer relationships – and thereby make profits in those lower-tax jurisdictions. This puts ‘bricks and mortar’ businesses, or those without global reach, at a disadvantage.

Digital services taxes (DSTs) are tax measures introduced since the late 2010s by over thirty countries, including the UK,[1] in an initial attempt to plug this gap in international tax rules that were designed in a pre-digital age. Each country’s DST aims to tax a slice of the overall revenues of large, global online businesses, according to how much revenue those businesses generate from sales and users in their jurisdiction.

DSTs are an imperfect ‘fix’: they run contrary to how taxes on corporate profits (rather than revenues) usually work; and they apply only to a particular sector, though sector-specific taxes are not unusual. Nonetheless, in the absence of agreement on implementing a global deal, brokered between governments by the OECD in 2021, that would have re-apportioned some of multinationals’ taxable profits to places where their users or customers are located (the ‘Pillar 1’ arrangement), many countries consider that DSTs remain necessary and fair.

How does the UK’s DST work?

Different countries’ DSTs have different rates and thresholds, and apply to different categories of online services. The UK DST is a 2% tax on revenues attributable to UK users.

It applies only to companies or corporate groups that

- provide social media services, an online search engine, or an online marketplace (thereby excluding, for example, streaming or cloud data services);

- have over £500m of revenue worldwide from any of these activities;

- of which at least £25m derives from UK users (the first £25m of DST-qualifying revenues are exempt from the DST).[2]

These conditions limit the tax to a small number of very large corporate groups: though HMRC initially identified 101 groups that might come within the scope of the DST,[3] figures released to TaxWatch via a Freedom of Information request indicate that after detailed assessment only 51 groups were judged to be within the tax’s scope, of which in 2023/4 (the latest year for which figures are available) only 41 submitted a DST tax return, and only 25 paid any DST tax in that year.[4]

The DST applies to revenue rather than profits, and companies can have substantial revenues but make small profits or even losses. In addition, there is a risk that due to differing DST designs in different jurisdictions, some revenues may be attributable to users in several jurisdictions with DSTs, resulting in double taxation. The UK DST contains some safeguards for these problems. First, to ensure that companies that are making a loss on their UK services do not incur tax, companies can also choose an alternative method of calculating their DST liability based on their UK operating margin rather than UK revenues.[5] Second, where the DST is paid by a UK-registered subsidiary company, in most cases it is a deductible expense against UK corporation tax liabilities.[6] Third, in an attempt to avoid taxation of the same revenues by multiple countries’ DSTs, taxpayers can apply for 50% relief on UK DST for revenues from cross-border transactions involving users from more than one DST jurisdiction.[7]

Due to the nature of a revenue tax, these safeguards may not prevent double taxation, or taxation in the absence of profits, as systematically as the conventional attribution of cross-border profits to different jurisdictions, for instance under double taxation treaties. They are nonetheless intended to approximate the same effect.

The UK’s DST entered into force in April 2020, with the first tax revenues being received in tax year 2021/22. Since DSTs were initially envisaged as a temporary ‘fix’ to be replaced by the (now deadlocked) global Pillar 1 tax arrangement, the UK government is obliged by legislation to conduct a review of the UK DST and lay it before Parliament by the end of 2025.[8]

International challenges to the UK DST

Since 2019 it has been US government policy to threaten tariffs against the UK and other countries with DSTs.[9] The US argues that because US-headquartered multinationals have historically been market leaders in social media, search, streaming and online retail, DSTs de facto discriminate against US businesses. Reports by the Office of the US Trade Representative since 2019 have gone further, arguing that various countries also intentionally designed DSTs to target US businesses. [10] We examine the reality of both these claims below.

Initially the US put its tariff threat on hold to allow more time for countries to agree the legal arrangements of the OECD ‘Pillar 1’ deal, which most countries have agreed would replace DSTs.[11] In February 2025, however, the US government renewed the threat of punitive tariffs against countries with DSTs and similar taxes,[12] while simultaneously signalling that it would withdraw from the OECD deal that was supposed to replace them.[13] The US’ withdrawal has deepened the political stalemate over the draft text of an international convention required to implement ‘Pillar 1’ taxes – making it even less likely that the ‘Pillar 1’ arrangement will now be implemented.[14]

The US administration’s 2025 budget bill (the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’) also authorised the US government to impose punitive additional tax rates, escalating over time, on governments, companies and individuals from countries with DSTs, including the UK.[15] This so-called ‘revenge tax’ provision was removed from the final act, partly because some countries such as Canada, India and New Zealand have cancelled their DSTs under US pressure; partly because the G7 nations, including the UK, capitulated to the US’ economic threat by promising to exempt US businesses from another part of the 2021 OECD tax deal;[16] and partly because the US Treasury Secretary himself, balking at the potential blowback on the US economy from such a measure, asked Congress to remove the ‘revenge tax’ provision.[17]

But the threat to the DST, and other UK taxes affecting large US tech businesses, has not gone away. The US retains the threat of punitive tariffs on countries with DSTs using powers in the US Trade Act.[18] In UK-US negotiations this year over trade and tariffs, the UK government reportedly discussed the possibility of reducing or abolishing the UK DST to appease US demands.[19] Announcing a sectoral trade agreement with the USA on 8 May 2025, Downing Street insisted that “[t]he Digital Services Tax remains unchanged as part of today’s deal”.[20] Twenty-four hours later, however, the Prime Minister suggested it was still under discussion: asked if he could guarantee that the deal would not mean any changes to the DST, he said: “[o]n digital services, there are ongoing discussions, obviously, on other aspects of the deal.”[21]

On 26 August 2025 the US President renewed the tariff threat, posting on his ‘Truth Social’ website that

Digital Taxes, Digital Services Legislation, and Digital Markets Regulations are all designed to harm, or discriminate against, American Technology. They also, outrageously, give a complete pass to China’s largest Tech Companies

The US President promised “substantial additional Tariffs on that Country’s Exports to the U.S.A., and institute Export restrictions on our Highly Protected Technology and Chips” if such taxes did not “end, and end NOW!”[22]

Figure 1: US President Truth Social post, 26 August 2025

Source: Truth Social via Internet Archive

Source: Truth Social via Internet Archive

The US online tech sector is advocating strongly for the US government to implement such measures against foreign DSTs. In a June 2025 letter to the US Treasury and Commerce secretaries coordinated by the Computer and Communications Industry Association (the online tech industry lobby group whose members include Amazon, Apple, Google and Meta)[23] industry representatives singled out Canadian and UK DSTs as “the largest burden on U.S. firms and the U.S. Treasury” amongst all countries’ DSTs. They urged the US Trade Representative (responsible for determining tariffs in response to foreign ‘discriminatory taxes’) to “pursue all options in responding to these longstanding barriers”. They also called on the US government not to conclude a trade deal with the UK unless the UK abolished its DST.[24]

(Asked to comment for this briefing, a UK spokesperson for the CCIA confirmed their support for this gamut of policy options against the UK, saying: “there are a range of options available to USTR in responding to discriminatory taxes, of which retaliatory taxes and tariffs are an important element, but by no means the only option. Indeed, per your question about a trade deal, making abolition of the DST a positive step to achieve a rules-based digital partnership that benefits both countries would be one of these options.”)[25]

The US online tech sector has advocated for tariff and trade measures against DSTs despite opposition from other business sectors. The Global Business Alliance, for instance, a leading advocacy body for over 200 international multinationals in the US, from Airbus to Siemens, strongly opposed the ‘revenge tax’ measure in the US Budget Bill, publishing a report estimating that it could reduce U.S. GDP by $100 billion annually and eliminate as many as 700,000 US jobs.[26]

DST revenues: present and future

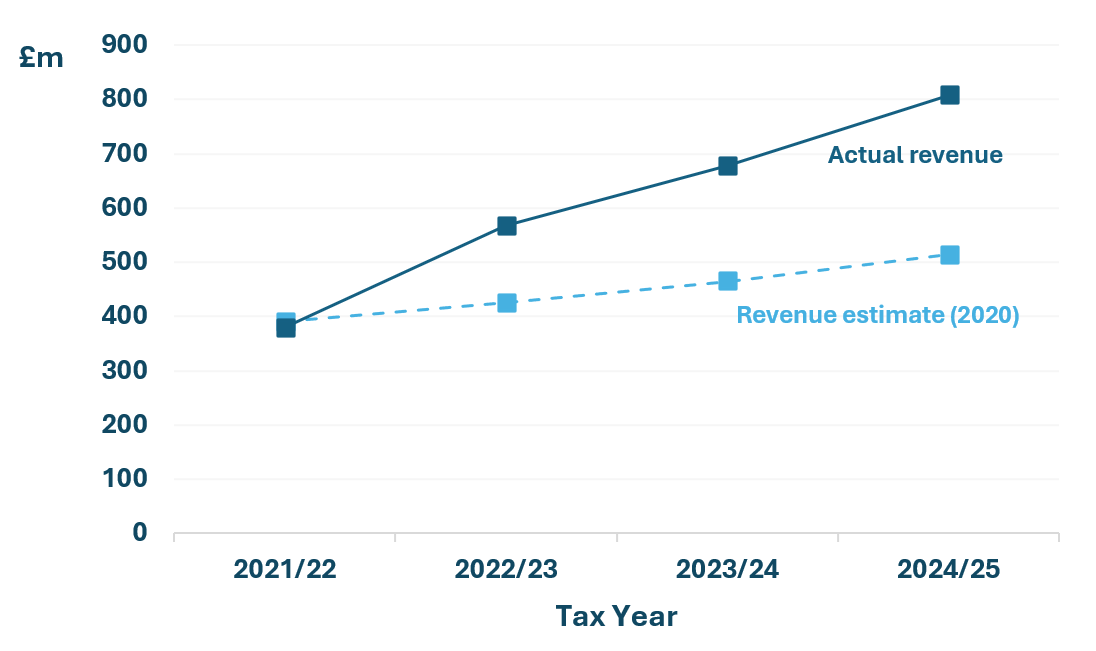

The UK DST has generated more revenue than initially expected. The UK Treasury originally estimated that DST revenues would rise to around £515m by 2024/5.[27] In fact, revenues have been nearly 60 percent higher than that, and have grown faster than expected (Figure 2). This is likely because more companies proved to be within the scope of the DST than the government had expected,[28] and also because of strong growth in UK online advertising and online retail sales (see below).

Figure 2: Original DST revenue estimate and actual revenue (£m)

Sources: UK HMRC policy costing (2020), UK HMRC tax receipts annual bulletin (2025)

Sources: UK HMRC policy costing (2020), UK HMRC tax receipts annual bulletin (2025)

Future tax revenues are always uncertain, dependent on changing economic and sectoral conditions. We also do not know what proportion of DST revenues derive from the different sectors that the tax covers (search, social media and online retail platforms).

However, the two main revenue sources for those digital services in scope of the UK DST – online advertising from search and social media; and revenue from providing online retail platforms – have consistently continued to rise in the UK for over a decade, and to rise faster than the rest of the UK economy (Annex 1). This strongly suggests that DST revenues will also continue to rise, becoming an increasingly significant slice of UK business tax revenues.

To estimate DST revenues during the expected term of this parliament (mid-2024 to mid-2029), we have used actual DST revenues for 2024/25, and have then projected trends for its increase in three different ways:

(i) Envisaging that DST revenues rise on trend with previous increases in DST revenues since the tax was introduced (we have excluded the first year’s revenue (2021/2) from the trend, since this is likely to have been unusually small as the tax was bedding in, and would otherwise skew upwards the subsequent trend);

(ii) Envisaging that DST revenues will rise in accordance with the past trend in UK digital advertising sales, as tracked by industry surveys conducted annually by the UK trade body for online advertising, the Internet Advertising Bureau UK (IAB UK),[29] which includes all major social media, search and e-commerce platforms.[30] We have looked separately at the trend in UK digital ad sales as a whole, and the subset of these ad sales by search providers;

(iii) Envisaging that DST revenues will rise in accordance with the past trend in UK online retail sales, tracked by the UK Office of National Statistics (ONS)[31] (we have confined the trend analysis to the period since June 2022, in order to avoid the dramatic above-trend bump in online retail during the Covid-19 pandemic from skewing our estimate of the long-term trend).

N.B. Neither the IAB UK nor the ONS are in any way responsible for our estimates or our use of their data.

Projections based on the past upward trend in UK digital ad sales, online retail sales and DST revenues themselves provide a range of estimates of future DST revenue increases (Figure 3). We have also examined the revenue projections by the UK’s Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR), updated most recently in March 2025.[32] The OBR projection is more optimistic about revenue growth than the projections we have produced based on industry statistics, but accords closely with the projection we have produced using past DST revenue trends, except for 2028/9 when the OBR is slightly more conservative. Annex I provides more information about the methods and data used.

Figure 3: Projected UK DST revenues, 2024/5 to 2028/9 (£m) Projection method 2024/5 (actual) 2025/6 (est.) 2026/7 (est.) 2027/8 (est.) 2028/9 (est.) Total projected DST revenue, 2024/5 to 2028/2029 (£m)

OBR forecast (March 2025) 800 900 1,000 1,100 1,100 4,900

(i) Change in DST revenues, 2022/3 to 2024/5 808 925 1,046 1,166 1,287 5,232

(ii) Change in UK digital ad sales, 2013 to 2024 808 877 967 1,057 1,147 4,857

[Search only] [808] [881] [960] [1,040] [1,119] [4,808]

(iii) Change in UK online retail sales, April 2022 to June 2025 808 848 883 918 953 4,409

Sources: see Annex 1

£0.9bn-1.1bn per annum is a relatively small proportion of all receipts from direct business taxes, which totalled £97.7bn in 2024/5.[33] Nonetheless, for scale, the actual and projected revenues in Figure 3 would cover the cost of training between 108,000 and 128,000 nurses during this parliament (for more details of this calculation see Annex II).

Myth-busting: who pays the DST?

The US government, the US tech industry, and other DST critics have argued that the UK DST is entirely,[34] ‘almost entirely’[35] or ‘primarily’[36] paid by US-headed tech multinationals: either by design,[37] or by default due to US companies’ dominance of the sectors to which the tax applies.[38] The US President has also recently claimed that DSTs exempt large Chinese tech companies.[39]

By design?

We have been unable to find any DSTs that by design exempt Chinese companies, or that specifically apply to US-headed groups. DSTs apply simply to corporate groups with significant numbers of users in a given jurisdiction, and large global revenues. Internal company documents reported in August 2025 by Reuters suggest that in Q2 2025, ByteDance’s revenues exceeded those of Meta for the first time:[40] in other words, on paper at least, the world’s number 1 social media company by sales is no longer a US company. Chinese and other non-US tech and online retail companies’ revenues in markets with DSTs are also growing. Major online marketplaces and content providers used by UK consumers now include those headquartered in China, Singapore or related financial centres,[41] from Shein and Temu to TikTok. These developments make it very likely that Chinese-headed internet firms are beginning to come into scope of DSTs, including in the UK. Some UK-headquartered online marketplaces, like Auto Trader, also now pay UK DST.[42]

Claims that the UK DST was designed to target US companies are based on evidence presented in a 2021 US government investigation into the UK DST conducted by the Office of the US Trade Representative (USTR).[43] This investigation report claims that “Statements by UK Officials Show that the Digital Services Tax Is Intended to Unfairly Target U.S. Companies”.[44] This section quotes statements by five ‘UK Officials’: comments by then Conservative Prime Minister Boris Johnson and the Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond (whose statements do not mention US companies at all); and tweets/Facebook posts by three opposition MPs — Jeremy Corbyn MP, the then leader of the Labour Party; John McDonnell MP, then shadow chancellor; and Margaret Hodge MP, a Labour Party member of parliament — who were not government officials at all but opposition politicians, and could not have been responsible for either designing or introducing the DST. The US government reports claims that these (opposition) politicians’ statements “strongly point to an intention [by the UK government] to target U.S. companies with special, unfavorable tax treatment.”[45]

To support its claims that the UK DST discriminates against US-headed companies, the US Trade Representative report also argues that it has been unable to identify any UK-headed search engines, online retail platforms or social media providers that meet the revenue thresholds to fall within the scope of the UK DST.[46] This is now demonstrably not the case: revenue authority statistics obtained by TaxWatch show that 37 percent of the companies or corporate groups now assessed to be liable for the UK DST are not US-headed companies (see below). These include at least one UK online retail platform, which declared DST liability in its 2024/5 accounts.[47]

De facto?

Claims that the UK DST de facto targets US companies have been made without any data about who actually pays the DST. HMRC does not release names or details of taxpayers. Nor in most cases do the published financial accounts of subsidiaries of major tech multinationals declare the amount of DST that they pay.[48] Some commentators have pointed to figures published by the National Audit Office (NAO) in 2022, which covered only the first year of the DST (2021/2), when only 18 corporate groups paid the DST (compared to 25 in 2023/4). These figures suggested that 90 percent of DST revenues in that first year came from five corporate groups, which the NAO’s report did not name, but which commentators have almost universally assumed were the ‘Big Five’ US internet giants (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta and Microsoft).[49]

HMRC has declined to release any more recent figures for the proportion of DST revenues are paid by subsets of its taxpayers, nor what proportion are paid by groups headquartered in different jurisdictions.[50] However, TaxWatch recently obtained via UK Freedom of Information laws the first ever public statistics about the number of corporate groups liable for the UK DST that are headquartered in and outside the United States.[51]

These figures (Figure 4) show that:

- 37 percent of the companies or corporate groups assessed to be within the scope of the UK’s DST are not headquartered in the US

- 34 percent of those which submitted a DST return in 2023/24 (the latest year available) are not headquartered in the US

- 28 percent of those which paid a DST liability in 2023/24 are not headquartered in the US.

(Note: these three figures differ because some corporate groups may now be in scope of DST, but did not have DST liabilities in previous years. In addition, some corporate groups with DST liabilities in 2023/24 may for legitimate reasons not yet have submitted their tax returns for that year; or may have submitted a DST return but not yet paid their DST liabilities. They may also have submitted a DST return asserting that they did not have any DST liability in a given year).

Figure 4: Numbers of corporate groups within the UK DST regime

Tax year | US-headquartered | Non-US-headquartered |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| In-scope of DST | 2024/5 | 32 | 19 |

| Submitted DST tax return | 2022/3 | 28 | 13 |

| 2023/4 | 27 | 14 | |

| Paid a DST liability | 2023/4[52] | 18 | 7 |

Source: HMRC, response to FOI request, 28 May 2025

In short: claims that the UK DST de facto targets exclusively or almost exclusively US-headed tech companies are essentially based on a 2022 report, combined with suppositions about the companies likely in-scope of the DST that have not adjusted to reflect changing geography of the internet. It is possible, even likely, that US-headed groups still provide a greater proportion of DST revenues by value than their numerical proportion, in proportion to their larger revenues in markets with DSTs. (In response to this report’s findings, a UK spokesperson for the CCIA made this point, saying: “While that pattern may have changed to some extent since [the 2022 report], we still believe that the tax is overwhelmingly (90%+) borne by American companies (as our note says) in line with broadly-available statistics on the shares of activity in each segment reported in the business press.”)[53]

To argue that this discriminates against US companies, though, is to argue that a flat-rate tax discriminates against taxpayers simply because they make more taxable profits or revenues.

Conclusion

The UK’s Digital Services Tax was never intended to be a permanent solution to the problem of large tech companies being able to reduce or avoid their taxable presence in the UK. However, with the US administration now also opposed to the international profit-apportionment arrangement that the US government had previously argued should replace DSTs,[54] the DST ‘fix’ remains the UK’s primary de facto solution to this problem in international taxation.

As the tech sector grows – especially beyond the US – the UK DST is likely to become a more significant proportion of tax revenues from multinational businesses doing business in the UK.

Ironically, given opposition from the US government and the US tech industry, abolishing the UK DST would in part benefit Chinese and other non-US internet giants that are amongst the tech sector’s fastest-growing members.

Annex I: estimating future revenues from the UK DST

1. The UK DST is a percentage of revenues from sales of goods and services (primarily advertising and sales commissions) linked to UK users of search engines, social media apps and online retail platforms. There is no direct measure of these UK user-linked sales in published government statistics, and DST payors mostly do not disclose their DST expense in published accounts. However, figures are available over time for UK online retail sales and UK online advertising sales. These data series may provide proxies for changes in DST-covered revenues. Since we do not know what proportions of UK DST revenues derive from advertising vs. sales commissions/fees, we have produced a range of estimates by applying the past trend in these two data series separately to total DST revenues.

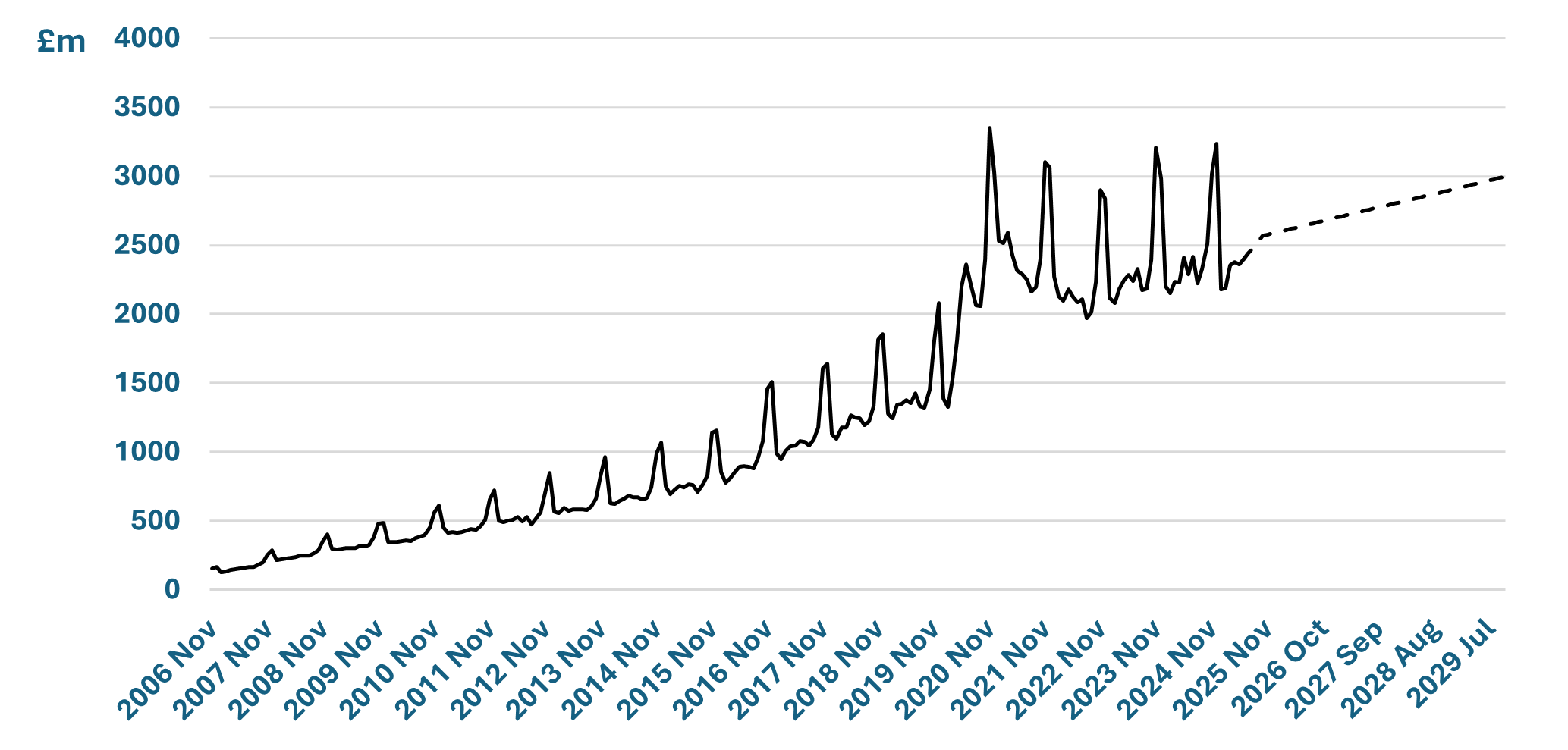

2. UK online retail sales have been tracked monthly by the Office of National Statistics since November 2006. At the time of writing, the latest available statistics in the series are for June 2025.[55] UK online retail sales have consistently risen over time, but the pandemic period (2020-22) showed an unusual above-trend increase (Figure 5), before settling to a lower rate of growth from 2022 onwards. We have therefore only used the trend from April 2022 onwards in projecting future growth in online retail sales. We have used a linear least-squares method via the Excel LINEST/TREND function to estimate the trend from April 2022 to June 2025, and to project future change to 2029, assuming that the May 2022 to June 2025 trend continues (Figure 5). Our projection, applied to DST revenues (see below) sums the monthly trend to annual figures for online retail sales, thereby smoothing the seasonal variation evident in Figure 5.

Figure 5: UK average weekly online retail sales, Nov 2006 – Oct 2029 (£m)

Source: Office of National Statistics plus projection post June 2025

Source: Office of National Statistics plus projection post June 2025

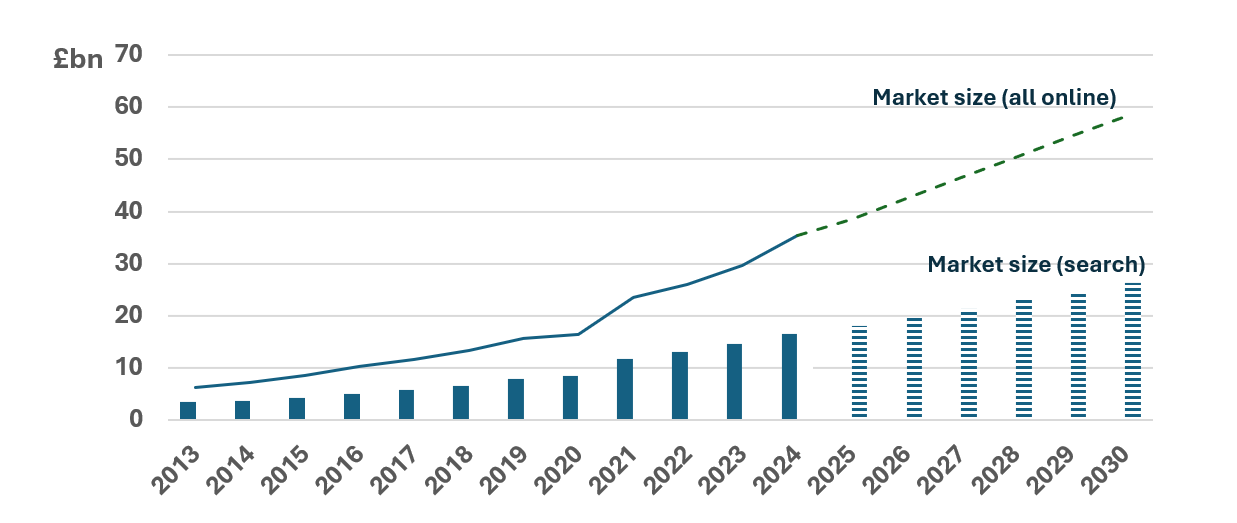

3. UK online ad sales are tracked annually from its members by the UK Internet Advertising Bureau (UK IAB), the industry group for online advertising which includes all major US and UK social media and search providers.[56] UK IAB produces figures for the size of the UK online advertising market as a whole, and solely for search. These statistics are highly likely to encompass significant DST payors, since according to the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority in 2019 Google had an over 90% share of the UK online search advertising market, and Meta/Facebook had over 50% of the UK online display advertising market, together accounting for 80 percent of the entire UK online advertising market.[57] As with UK online retail sales, we have estimated the growth trend from 2013 to 2024 using the Excel LINEST/TREND linear least-squares regression function, and have then used this trend to project future growth in UK online advertising as a whole, and for search only (Figure 6).

Figure 6: actual and projected online advertising sales, 2013-2030 (£bn)

Source: IAB UK, various dates, plus projection post-2024

Source: IAB UK, various dates, plus projection post-2024

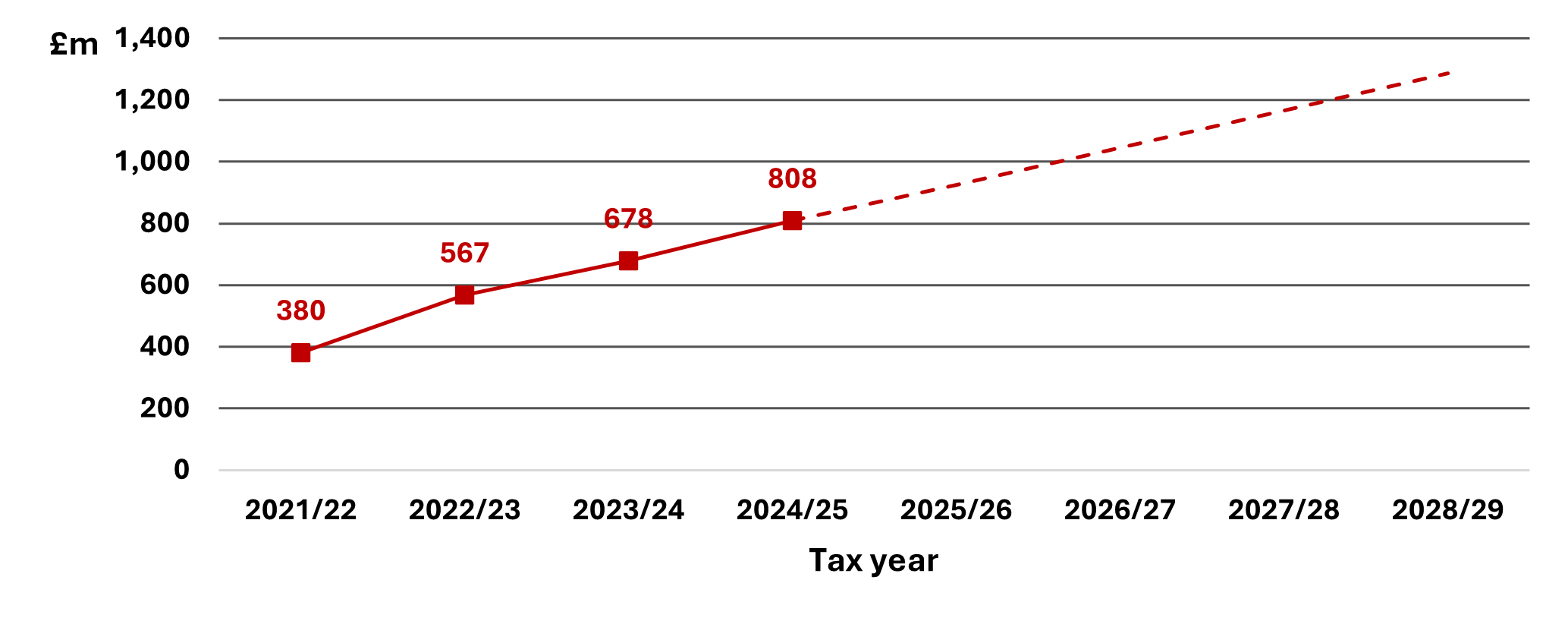

4. Finally, given the consistent upward and above-GDP growth trend of both UK online retail sales and UK online advertising sales, growth of UK DST revenues themselves may also be expected to continue. Directly measuring the growth trend of UK DST revenues themselves may thus also be an estimation method for future DST revenues. (This is the method which the UK’s Office of Budget Responsibility appears to have used – see Figure 3 above – with some modifications which assume an eventual slowdown in DST revenue growth towards the late 2020s). Again, we have estimated the past trend in DST growth using the Excel LINEST/TREND function, excluding the first year of revenue which would be expected to be lower than trend while the tax regime bedded in and some in-scope taxpayers had not yet submitted tax returns or made payments; and projected future DST revenue growth along the same trend (Figure 7).

Figure 7: DST revenues, actual and projected, 2021/2 to 2028/9 (£m)

Source: HMRC revenue statistics plus projection

Source: HMRC revenue statistics plus projection

5. We have then applied the projected annual growth in (i) UK online retail sales, (ii) UK online advertising sales, (iii) UK online advertising sales (search only), and (iv) DST revenues themselves, to 2024/5 DST revenues. This produces forecast DST revenues along four different potential trends (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Actual and projected DST revenues, 2024/5 to 2028/9

Actual DST revenue | Forecast DST revenues based on past DST revenue growth | Forecast DST revenues based on forecast growth of internet retail sales |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tax year | Revenues (£m) | Change (%) | Revenues (£m) | Change (%) | Revenues (£m) |

| 2021/2 | 380 | ||||

| 2022/3 | 567 | ||||

| 2023/4 | 678 | ||||

| 2024/5 | 808 | 100 | 808 | 100 | 808 |

| 2025/6 | - | 115 | 925 | 105 | 848[58] |

| 2026/7 | - | 129 | 1,046 | 109 | 883 |

| 2027/8 | - | 144 | 1,166 | 114 | 918 |

| 2028/39 | - | 159 | 1,287 | 118 | 953 |

| Total 2024/5 to 2028/9 (£m) | - | 5,232 | 4,409 | ||

Forecast DST revenues based on forecast growth of UK digital ad spend | Forecast DST revenues based on forecast growth of UK digital ad spend - search only |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Tax year | Change (%) | Revenues (£m) | Change (%) | Revenues (£m) |

| 2021/2 | ||||

| 2022/3 | ||||

| 2023/4 | ||||

| 2024/5 | 100 | 808 | 100 | 808 |

| 2025/6 | 109 | 877 | 109 | 881 |

| 2026/7 | 120 | 967 | 119 | 960 |

| 2027/8 | 131 | 1,057 | 129 | 1,040 |

| 2028/39 | 142 | 1,147 | 138 | 1,119 |

| Total 2024/5 to 2028/9 (£m) | 4,857 | 4,808 | ||

Sources: HMRC revenue statistics, IAB UK, ONS, plus projections. Note : online ad sales figures are given/calculated per calendar year, and then applied to revenue per tax year e.g. revenue projections for tax year 2024/5 are based on projected ad sales for calendar year 2024. Over multiple years this does not significantly affect the trend.

6. One obvious question is why we do not simply use the OBR’s projection for future revenues. The OBR’s projection falls within the range of estimates we have projected based on industry statistics and past DST revenues (Figure 9), and we have included it above (Figure 3) for comparison. The OBR projection accords most closely with our projection using past DST revenue trends, except for 2028/9 when the OBR is slightly more conservative. However, the OBR projection – based it appears primarily on past DST revenues – is more optimistic about revenue growth than our projections incorporating industry statistics. The growth rate of any tax’s revenues may be expected to stabilize after the first few years of the tax’s introduction, during which revenue typically grows faster because taxpayers are gradually identifying themselves and filing returns for past years. Since the UK DST was only introduced in 2020, we have therefore considered it prudent to use industry statistics, rather than past tax revenues alone, to project future revenue growth. These produce a more conservative lower bound for our estimate than the OBR, though it is notable that previous OBR projections have historically underestimated DST revenues. It is possible that our more conservative estimates are also underestimates.[59]

Annex II: Estimating the cost of training nurses

1. Public sector staff costs are a blunt but illustrative way of showing the scale of tax revenues against public spending. In this example, we take the highest forecast for DST revenues (based on past UK DST revenue growth) and lowest forecast (based on forecast growth of UK internet retail sales), as shown in Figure 9. For each year from 2024/5 to 2028/9 we compare the forecast annual DST revenues with estimates for the cost of training new nursing staff.

2. Costing of training nursing staff: research commissioned by the Royal College of Nursing from the economics consultancy London Economics in 2023 estimated that the average cost of training a nurse was £37,287.[60] We assume that this cost rose (or will rise in future years) with price inflation, using Bank of England price inflator figures[61] for 2024 and 2025 and then conservatively assuming 4% annual cost inflation in future years.

3. Figure 10 shows how these costs compare against forecast DST revenues each year. The number of new nurse trainings whose cost is equivalent to forecast DST revenues are between 108,000 and 128,000. According to NHS staffing statistics, at the end of 2024 there were 436,133 nurses, midwives and health visitors and related support staff working in the NHS in England, Scotland and Wales (figures for Northern Ireland are not included in these statistics).[62]

Figure 9: estimated number of new nurses’ training whose cost is equivalent to forecast DST revenues, 2024/5 to 2028/9

Tax year Estimated average cost of training new nurse (£) Forecast/actual DST revenues (low bound): equivalent number of trainings Forecast/actual DST revenues (high bound): equivalent number of trainings

2024/5 37,660 21455 21455

2025/6 39,151 21651 23635

2026/7 40,717 21679 25685

2027/8 42,346 21672 27543

2028/9 44,040 21634 29220

TOTAL 2024/5 to 2025/6 108,091 127,538

Sources: RCN/London Economics, forecasts of DST revenues (see Annex 1)

References

[1] Jacinta Caragher, ‘Digital Services Taxes global tracker’, VAT Calc, 8 July 2025.

[2] HMRC, Digital Services Tax Manual: DST01200 – Overview of DST Liability, 19 March 2020 updated 31 July 2024.

[3] National Audit Office, Investigation into the Digital Services Tax, Session 2022-23, 23 November 2022, HC 905, p. 9.

[4] HMRC response to Freedom of Information request from TaxWatch, 28 May 2025 (FOI2025/51253).

[5] HMRC, Digital Services Tax Manual: DST01200 – Overview of DST Liability, 19 March 2020 updated 31 July 2024.

[6] HMRC, Digital Services Tax Manual: DST47100 – UK CT Deductibility of DST Liability, 19 March 2020 updated 31 July 2024.

[7] HMRC, Digital Services Tax Manual: DST43200 – Cross Border Relief Claim, 19 March 2020 updated 31 July 2024.

[8] Finance Act 2020, Part 2, s.71.

[9] Office of the US Trade Representative, Section 301 – Digital Services Taxes (n.d.).

[10] Office of the US Trade Representative, Section 301 – Digital Services Taxes (n.d.).

[11] Office of the US Trade Representative, ‘Proposed Action in Section 301 Investigation of the United Kingdom’s Digital Services Tax’, US Federal Register Vol. 86, No. 60, 31 March 2021, pp. 16829-32.

[12] The White House, Defending American Companies and Innovators From Overseas Extortion and Unfair Fines and Penalties: memorandum for the Secretary of the Treasury, the Secretary of Commerce, the United States Trade Representative, the Senior Counselor to the President for Trade and Manufacturing, 21 February 2025.

[13] The White House, The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Global Tax Deal (Global Tax Deal): memorandum for the Secretary of the Treasury, the United States Trade Representative, The Permanent Representative of the United States to the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, 20 January 2025.

[14] OECD, Pillar 1 Update from the Co-Chairs of the Inclusive Framework on BEPS, 13 January 2025.

[15] Tax Foundation, ‘The Future of BEAT’, 24 July 2025.

[16] Tom Parks, ‘Section 899 – the art of the tax deal’, Charles Stanley, 18 July 2025.

[17] ‘US Treasury signals G7 deal excluding US firms from some taxes’, AFP, 27 June 2025.

[18] Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974.

[19] Pippa Crerar et al, ‘Starmer offers US big tech firms tax cuts in return for lower Trump tariffs’, The Guardian, 2 April 2025.

[20] 10 Downing Street, ‘Landmark economic deal with United States saves thousands of jobs for British car makers and steel industry’ (press release), 8 May 2025.

[21] Sam Francis, ‘Talks with the US over digital services continue, says PM’, BBC News, 9 May 2025.

[22] Donald J. Trump (@realdonaldtrump), post on Truth Social, 26 August 2025 (via archive.org).

[24] CCIA et al, ‘Association letter on Canada and UK DST’, 3 June 2025.

[25] Email communication from CCIA UK representative to TaxWatch, 4 September 2025.

[26] Global Business Alliance, The Revenge Tax Slowdown, June 2025.

[27] HM Revenue and Customs, Policy Paper: Digital Services Tax, 11 March 2020.

[28] National Audit Office, Investigation into the Digital Services Tax, Session 2022-23, 23 November 2022, HC 905, p. 9.

[29] For a summary of the 2024 IAB UK survey, see IAB UK, ‘IAB/PwC Internet Advertising Revenue Report: Full Year 2024’, 17 April 2025.

[30] IAB UK, ‘Member Directory‘ (n.d.).

[31] Office for National Statistics (ONS), Retail Sales Index internet sales, latest dataset to June 2025.

[32] UK Office of Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook – March 2025, Chapter 4, Table A.5.

[33] HMRC, HMRC tax receipts and National Insurance contributions for the UK (monthly bulletin, updated 21 August 2025). N.B. The £97.7bn includes revenues from corporation tax, the bank levy, the bank surcharge, the diverted profits tax, the digital profits tax, the residential property developer tax, the energy profits levy, the electricity generators levy, the economic crime levy and the petroleum revenue tax.

[34] CCIA, ‘CCIA Releases Data on Costs of Countries’ Digital Services Taxes on U.S. Companies’ (press release), 9 July 2025. This press release claims that DSTs “cost U.S. companies in countries like the U.K., France, Spain, and Italy over $9 billion from 2020-2024 alone, as calculated in findings released today”. The accompanying calculations (see here, Annex 1) attribute the entirety of UK (and other countries’) DST revenues to US companies.

[35] Dan Neidle, LinkedIn post, March 2025.

[36] Michael Devereux, ‘Is the Digital Services Tax a Tariff‘, Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation, 26 March 2025.

[37] The Whitehouse, Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Issues Directive to Prevent the Unfair Exploitation of American Innovation (21 February 2025).

[38] Dan Neidle, LinkedIn post, March 2025.

[39] Donald J. Trump (@realdonaldtrump), post on Truth Social, 26 August 2025 (via archive.org).

[40] Krystal Hu, Julie Zhu, Kane Hu, ‘TikTok owner ByteDance eyes valuation of over $330 billion as revenue surpasses Meta’, Reuters, 28 August 2025.

[41] Like many Chinese multinationals, the holding company of TikTok/Bytedance, Bytedance Ltd, is registered in the Cayman Islands: see Bytedance Ltd v European Commission (Case T-1077/23, Judgement of the General Court, 8th Chamber, 17 July 2024). Shein’s parent company Roadget Business Pte Ltd, is registered in Singapore (company number 201939698G). Temu’s parent company, PDD Holdings Inc, is registered in the Cayman Islands but lists its registered office as being in Dublin, Ireland: PDD Holdings Inc, Form 20-F, 28 April 2025.

[42] Auto Trader Group Plc, Full Year Results for the Year Ended 31 March 2025, 29 May 2025.

[43] For US tech industry representatives’ references to this USTR report, see TaxWatch, ‘Donald Trump claims the UK’s Digital Services Tax overwhelmingly targets US tech giants. New data obtained by TaxWatch shows it doesn’t‘, 5 June 2025.

[44] Office of the US Trade Representative (Executive Office of the President), Section 301 Investigation Report on the United Kingdom’s Digital Services Tax, 13 January 2021, pp. 13-17.

[45] Office of the US Trade Representative (Executive Office of the President), Section 301 Investigation Report on the United Kingdom’s Digital Services Tax, 13 January 2021, p.14.

[46] Office of the US Trade Representative (Executive Office of the President), Section 301 Investigation Report on the United Kingdom’s Digital Services Tax, 13 January 2021, pp. 13-17.

[47] Online car sales group Auto Trader, which declared a £10.2m DST charge in its operating expenses for the year to 31 March 2025. Auto Trader Group Plc, Full Year Results for the Year Ended 31 March 2025, 29 May 2025.

[48] One rare exception is the UK-headed online car sales group Auto Trader (see above).

[49] Michael Devereux, ‘Is the Digital Services Tax a Tariff‘, Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation, 26 March 2025; Mark Sweney, ‘UK’s digital services tax reaps almost £360m from US tech giants in first year’, The Guardian, 23 November 2022.

[50] HMRC response to Freedom of Information request from TaxWatch, 4 August 2025 (FOI2025/132244).

[51] HMRC response to Freedom of Information request from TaxWatch, 28 May 2025 (FOI2025/51253).

[52] HMRC provided the total number of groups that paid DST in 2022/3, but declined to break them down by headquarter location for confidentiality reasons.

[53] Email communication from CCIA UK representative to TaxWatch, 4 September 2025.

[54] Office of the US Trade Representative (Executive Office of the President), Section 301 Investigation Report on the United Kingdom’s Digital Services Tax, 13 January 2021, p.38.

[55] Office for National Statistics (ONS), Retail Sales Index internet sales, latest dataset to June 2025.

[56] For a summary of the 2024 IAB UK survey, see IAB UK, ‘IAB/PwC Internet Advertising Revenue Report: Full Year 2024’, 17 April 2025. We have taken previous years’ figures from annual IAB UK press releases back to 2013.

[57] Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), Online platforms and digital advertising Market study final report, 1 July 2020, p. 42.

[58] Forecast incorporates actual internet retail sales figures for May-June 2025.

[59] E.g. in March 2023 the OBR forecast DST revenues of £700m for 2024/5 (actual revenues were £808m), and forecast a rise to 900m by 2027/8, which it has this year revised upwards to forecast £1100m DST revenues in 2027/8. UK Office of Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook – March 2023, Chapter 4, Table A.5.

[60] Royal College of Nursing, ‘NHS has squandered billions on agencies that could have been used to hire over 31,000 nurses’ (press release), 6 December 2023.

[61] Bank of England, ‘Inflation Calculator‘ (n.d.).

[62] Adele Walker, ‘How many nurses are there in the UK?’, BMJ HealthCareers, 8 May 2025.

Main photo by camilo jimenez on Unsplash