Last week’s Budget underscored the government’s struggles to balance the books without raising taxes or cutting services.

Yet one source of lost revenue – offshore tax evasion – remains persistently under-policed and under-discussed. It appeared nowhere in the £2.6 billion raft of Budget measures aimed at closing the ‘tax gap’ of avoided and evaded tax. And at the very moment the Chancellor was searching for fiscal headroom, just across Parliament Square at the Joint Ministerial Council (JMC) of the Overseas Territories (OTs), UK ministers and representatives of some of the world’s most important offshore financial centres were presiding over another year of drift and broken promises on tackling offshore secrecy.

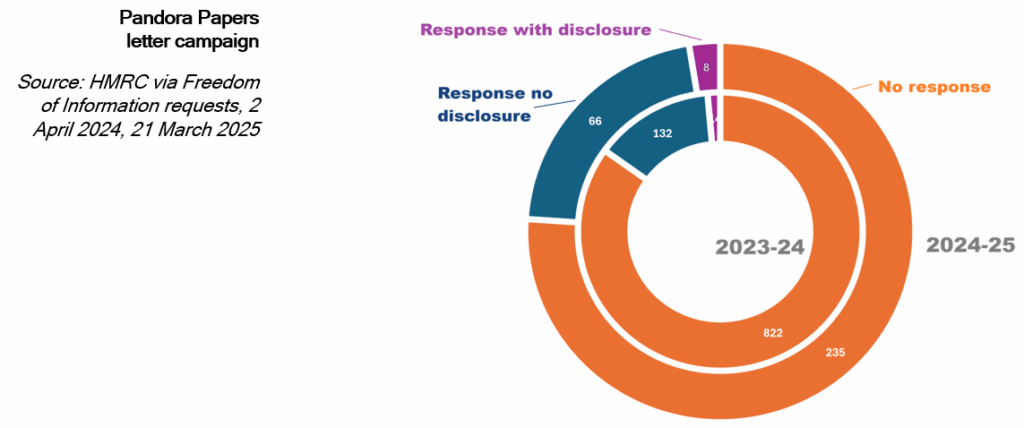

TaxWatch’s new State of Tax Administration 2025 (SOTA 2025) report also uncovers chronic under-resourcing and under-enforcement within HMRC’s offshore compliance efforts, despite repeated government promises to crack down. Using Freedom of Information (FOI) data and official disclosures, we found that HMRC’s “integrated” approach to offshore risks masks underpowered staffing, limited use of penalty powers, and scarce prosecutions.

The UK’s limited offshore enforcement capacity

An FOI response confirms that HMRC had only about 643 full-time equivalent staff specifically dedicated to offshore tax compliance in 2023/24. Out of a Customer Compliance Group of over 26,000 people, just 2.5% of compliance staff are focused exclusively on offshore issues. The Chancellor’s Spring Statement promised a dedicated unit of 400 staff focused on ‘wealthy offshore cases’ including “experts in private sector wealth management”, but it is unclear whether these staff will be new or redeployed from other roles.

Without knowing the full scale of offshore evasion, it’s difficult to say definitively that HMRC’s offshore compliance resourcing is too small. But it is reasonable to say that:

- A 600-strong unit looks modest against an offshore asset base of at least £850 billion just in foreign account holdings;

- The Treasury’s projected £500m additional yield from the upcoming expansion of 400 staff appears unambitious when even a single concealed offshore structure (e.g. the offshore trusts of Bernie Ecclestone) can hide hundreds of millions in untaxed income and gains.

The numbers speak for themselves: whatever HMRC’s actual offshore tax gap figure, the scale of the asset base and the size of the most complex cases suggest a substantial mismatch between risk and investigative capacity.

There is also a circular logic at play. If HMRC works from its published estimate of just £300m in tax evaded in offshore accounts, then its deployment of limited staff appears rational. But if that estimate is itself far below reality – and even below HMRC’s own estimates of offshore ‘tax at risk’ whose unpublished existence TaxWatch uncovered earlier this year – then it systematically under-powers HMRC’s resourcing choices.

Underused Powers: Penalties That Barely Bite

Since the shake-up of the Panama Papers in 2016, HMRC has been given tougher tools to tackle offshore evasion . But TaxWatch’s SOTA 2025 report reveals a pattern of these powers gathering dust:

- Enabler Penalties (Finance Act 2016, Schedule 20): This regime, introduced in 2017, allows HMRC to fine accountants, lawyers or other “enablers” of offshore tax evasion. HMRC has not issued a single penalty under this power since its inception.

- “Requirement to Correct” Offshore Penalties: In 2018, HMRC rolled out tough Failure to Correct penalties (Schedule 18, Finance (No.2) Act 2017) – 200% fines for taxpayers who didn’t voluntarily correct undeclared offshore income by the deadline. According to FOI data, HMRC has issued approximately 2,500 Failure to Correct penalties since 2018/19, totalling about £90 million. While this indicates some use of the power, questions remain about follow-through. The average penalty (~£36,000) suggests it primarily hit mid-level evaders; whether truly major offshore tax dodgers have faced these fines is unclear.

- Not a single person has been criminally prosecuted under the “strict liability” offence for offshore evasion (166 Finance Act 2016).

- Offshore Asset Moves: The UK introduced special penalties for those who shift assets to hide them from HMRC (Schedule 21 FA 2015 and Schedule 22 FA 2016). Yet HMRC data show only around 350 such asset-concealment penalties have been levied in total, raising roughly £0.5 million. That’s an average of just £1,400 per penalty, indicating these fines are both infrequent and very small.

This pattern does not necessarily show leniency, but it does indicate scarce use of some parts of HMRC’s toolkit. Parliament’s Public Accounts Committee put it bluntly: HMRC “must be bolder”. The current approach still doesn’t do enough to shift behaviour among the highest-risk offshore actors or the professional enablers who facilitate them.

Overseas Territories: Secrecy Havens Undermining Enforcement

These enforcement gaps are especially problematic given the environment in which offshore evasion thrives, including in some of the UK’s own Overseas Territories (OTs). The OTs, including jurisdictions like the British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, and Bermuda, are frequently implicated in tax avoidance and evasion schemes, offering secrecy and complex offshore structures to shield untaxed income. Over the summer, TaxWatch’s ‘mystery shopper’ exercise found that several OTs have failed to live up to their promises of corporate ownership transparency. The communiqué from last week’s Joint Ministerial Council of the Overseas Territories (JMC) confirms a little progress. TaxWatch had found that St Helena’s corporate transparency register, lauded by ministers, didn’t yet exist. The territory has now joined Gibraltar and Montserrat in delivering a fully public register. It can be done.

But St Helena and Montserrat are tiny jurisdictions: the former has only around 200 companies on its corporate registry. Much more significant offshore centres like the Cayman Islands and Turks and Caicos have introduced “legitimate interest” access systems with last-minute increases in costs and (in the case of the Turks and Caicos) punitive legal restrictions on sharing any of the information received from the registry, rendering access by many third parties almost meaningless.

Meanwhile, jurisdictions like the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda and Anguilla remain without operational registers at all, despite promising to introduce them over a decade ago. Last week’s JMC communique simply ignores the Overseas Territories’ previous 2024 commitment to yet another ‘final final deadline’ of June 2025 as if it never happened. It suggests that timelines are now slipping to 2026 at the earliest. Way back in 2018 Parliament mandated the government to introduce an ‘Order in Council’ – UK legislation applying to the Overseas Territories – instituting such registers directly if they didn’t appear within two years. The situation is becoming farcical. At last week’s JMC both UK ministers and the Overseas Territories’ premiers yet again simply ignored this Parliamentary requirement, and a decade of broken promises. Instead, they simply “note[d] commitments by Anguilla, Bermuda and the British Virgin Islands, to continue delivery of their registers“, promised UK technical support “if requested“, and suggested a progress review in early 2026.

Of course, public or ‘legitimate interest’ access to information about the ownership of offshore companies is not the same as tax authorities’ access to offshore information. Nonetheless HMRC’s own casework suggests that corporate ownership data remains an important tool for tax enforcement too. The most significant UK offshore evasion prosecution of 2024-25, highlighted in HMRC’s Annual Report, involved Gibraltar and BVI companies whose ownership was revealed in the Panama Paper leak.

Time for Action: Scrutiny, Resources, and Real Consequences

The fact that this year’s Joint Ministerial Council took place in the very same week as the UK Budget underscores a simple but unavoidable truth: offshore tax evasion is now a fiscal issue as much as it is an integrity issue. The Treasury is battling a structurally high deficit, rising demand for public spending, and limited political space to raise headline tax rates. In that environment, closing the offshore tax gap is not optional. It should be a core component of any credible plan to stabilise public finances.

The Ecclestone case in 2023 demonstrated just how much untaxed wealth can be concealed offshore when transparency is weak and enforcement lacks the capacity to keep pace. A single concealed trust (worth an estimated $650 million) resulted in the largest ever UK fraud settlement by an individual. And while Ecclestone is undoubtedly a big fish, he is almost certainly not alone: he is just the one who was caught.

Recovering this potential revenue requires more than rhetoric and diplomatic platitudes. It requires transparency in the Overseas Territories, where secrecy structures and inaccessible beneficial ownership systems continue to frustrate tax enforcement. It requires a well-staffed HMRC, with enough specialists to investigate complex offshore structures, not just send nudge letters. And it requires HMRC to actually use the enforcement tools Parliament has given it, from enabler penalties to strict-liability offshore prosecutions, rather than leaving them dormant.

Without those three pillars, the UK will continue to leave significant sums uncollected, as the Treasury struggles to close the deficit.